It turns out this has happened. It happened in the 1870’s, but similar patent mechanics apply today. Weaknesses in 1870’s patent law allowed ruthless operators to collect “license fees” from ordinary farmers who happened to be using shovels. The case is described by Gerard Magliocca (Blackberries and barnyards: Patent trolls and the perils of Innovation, Notre Dame Law Review, June 2007). [See Appendix 1 for more details].

HOW DID THE 1870s SHARKS OPERATE?

The 1870 Patent Act loosened the criteria for filing patents. Pure design elements could now be patented, rather than functional elements. In other words, tiny (even ornamental) changes to basic designs could be patented and the patents enforced, and it was extremely difficult to know if a given product actually infringed the patent. Magliocca summarized the problem as being that “almost any farm tool could be classified as a design”.

This was quickly abused by patent sharks (as they were called then). By patenting tiny changes to essential equipment such as shovels, they could demand royalties, targeting individual farmers. Whether or not the cases had any actual merit, the farmers could not afford lawyers. They always caved in and paid a “licensing fee” of $10-$100 (real money in 1875). According to this site, ten dollars would have been a week’s salary for an urban fireman. In a rural economy, this would have been a proportionately much larger sum of money. Painful but not ruinous.

(I want to make a personal comment here. I do not consider patents as such to be the evil issue here. If someone uses significant money to develop, say, a truly new composite-material shovel that weighs a fraction of current shovels, they are entitled to protect it. It may not sound ethically nice, but at least it is not gaming the system, in the way that trolling is).

According to Magliocca, USPTO practices were changed during the late 1880’s so that pure design elements could no longer be patented. Shark activity was thus no longer profitable.

WHAT ALLOWS TROLLS TO THRIVE?

Magliocca sees direct parallels to today’s trolling situation, especially in software and business patents. He suggests three criteria that breed trolling behavior.

1. Substitution effect. It must be extremely difficult to find a substituting solution, either by bypassing the patents or by using a competing technology. Currently, software is dependent on multiple interacting modules, and redesigning one module can be too difficult to be realistic. On the other hand, in the 1870s, “there are only so many ways to design a shovel”. Once a patent had been granted, much anything could be alleged to infringe it. Since farmers needed shovels, they were open to attack.

2. Marginal improvements. When almost all patents look almost the same, it is difficult to know whether one is infringing or not. This is true of today’s software patents; it was true of design elements for shovels. When one has no prior way of actually knowing whether an infringement has taken place, going to court is a huge risk.

3. Cheap technology. Trolling only makes sense if it is very cheap to file and maintain patents, and owning just one critical patent can bring the targeted system to a halt. In the 1870’s the problems were due to the loose standards for patenting. Today, systems are highly integrated, and just one patent can block an entire system. In both cases, a strong “portfolio” could be created by just owning one single patent.

Cheapness is also related to the ability to hold on to patents for a long time. In the 1870s, “inventors” could patent small design elements, and then allow the patents to stay inactive until they saw them actually being used. Currently, this practice is discouraged by making maintaining a patent more expensive over time. However, Magliocca doubts whether the cost currently rises sharply enough. See Appendix 2 for details.

COULD 1875 BE REPEATED IN 2015?

Patent weirdness today get the most press in areas which are, in my opinion, socially irrelevant. We could survive without pinch-and-zoom user interfaces on touchscreens. We could not survive without water. Could trolls start to interfere with, say, access to water?

I will focus on sensor systems needed to monitor and optimize irrigation. Such ensors are a crucial part of controlling irrigation and conserving water. I will focus concretely on a patent which I have analyzed already (see Troglodyte: Cleantech 2). That patent is only one specific sample; there could be significantly worse ones.

1. Substitution effect. This might not seem like a severe risk, as a variety of sensor technologies that can be used. However, patents in the core of data transmission protocols are difficult to bypass because of their very generality, and because a single patent on a small detail can block an entire complex system. The Cleantech 2 patent certainly is in the category.

2. Marginal improvements. To exaggerate a little, all patents these days look alike. A small company won’t have the time or competence to estimate whether a case is valid. (Bizarrely, trying to do so could actually make things worse. If an infringement is judged to be “willful”, courts may triple the damages. In other words, if a company does try defend itself, in principle it risks being punished three times more severely. It is a Catch-22). An average company confronted with the Cleantech 2 patent probably would have no idea what to do.

3. Cheap technology. Patenting is cheap compared to the possible profits (see Appendix 2). And the USPTO is in serious trouble with spurious patents. Companies can now file spurious patents in critical areas, and keep them quietly hidden away. The Cleantech 2 patent is a good example. It may (at least partly) be in force for the next twenty years. If someone during that time develops a good real-time system for optimizing irrigation using rain sensors, the patent could come to haunt them.

I truly don’t know if we could see a repeat of 1875. Magliocca’s criteria do seem to be satisfied. The magnitude of the risk is completely impossible to predict. It could lead to severe disruptions in the development of irrigation technologies; it could be a minor irritant that slightly raises licensing costs; or, nothing at all might happen.

However, the right time to start preparing for potential attacks is now, before litigation (or threat of litigation) has even begun. Whether anything can actually be done I do not know; but being unprepared is the worst possible option.

——————————————————————————————————-

APPENDIX 1: STATISTICS

It appears that Magliocca’s paper is the only major study of that case, and the subjective description is largely based on one historical paper from the 1940’s (however, the paper is backed by extensive legal references). For the sake of general skepticism, I decided to see whether there are other sources that would support that description.

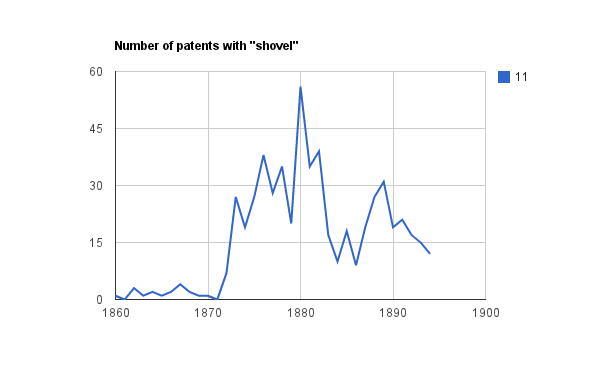

I made a Google Patents search for patent applications with the term “shovel” between 1860 and 1895 (Figure 1). There is indeed a dramatic peak after 1870, decreasing in the 1880’s. (I have no explanation for the secondary peak before 1890).

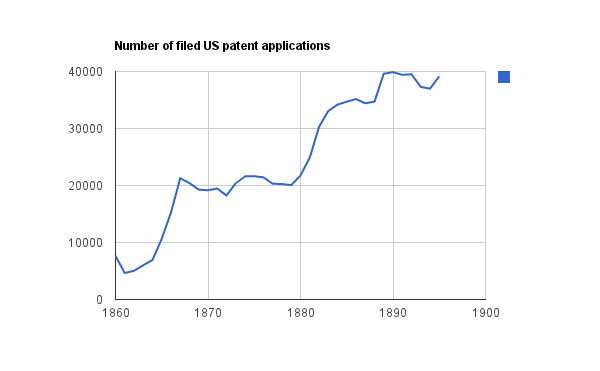

It is necessary to consider whether the growth could be due to general trends in patenting after 1875, rather than the specific shark effect. Figure 2 shows the number of patent applications, from USPTO statistics. There is more or less consistent growth throughout the same period. The peak in “shovel” applications is not related to any general growth of patent applications. The statistics are consistent with the shark hypothesis.

Figure 1: Number of patent applications with keyword “shovel”

Figure 2: Overall number of patent applications

——————————————————————————————————————

APPENDIX 2: HOW CHEAP IS PATENTING, ACTUALLY?

[Edit 30.8.2012: It was pointed out by an experienced reader that a more realistic cost for getting and maintaining a patent for 20 years is closer to 75 kUSD than 15 kUSD, if done properly. I accept that the estimate below is unrealistically small. However, if a higher cost estimate is used, then part of my point is made stronger: doubling the lifetime of the patent only adds some 5-10% to the overall cost].

From the USPTO’s current fees, filing a patent costs in the ballpark of 1500 USD. If the patent is granted, an issue fee of about 1700 USD must be paid. There can be various hard-to-predict fees which may raise the cost considerably.

In order to maintain the patent, maintenance fees must be paid: 1100 USD at 4 years, 2900 USD at 8 years, and 4700 USD at 12 years. The patent is then valid for 20 years. (The prices can be halved for small entities such as individual inventors). The absolute minimum cost to maintain a patent for 20 years is in the ballpark of 12,000 USD. A practical estimate is at least 15,000 USD, including patent attorney fees.

Magliocca notes that the purpose of the maintenance fees is to make it sharply more expensive to maintain patents for long periods. However, he suggests the rise is not sharp enough. Indeed, given the the initial filing phase also includes requires the patent application to be written by a patent attorney (not cheap), a good ballpark estimate is that the patent has already cost at least 6000 USD by the time of the first renewal, and there are no significant attorney fees after that. A large part of the money has thus already been spent up front.

In practice, maintaining a patent for eleven years easily costs about 10,000 USD, while maintaining it for the whole twenty years costs only 5,000 USD more. This does seem like a no-brainer: if there is any potential, one might as well go the full twenty years.